Archive

Rome and the Collapse Paradigm

The collapse of the Roman Empire is one of the most notorious and most extensively studied cases of societal collapse in human history. Several causes have been attributed to having contributed to the demise of the empire, but no single cause by itself has been widely accepted as being the cause. Typical explanations are thus:

–Barbarian Invasions

–Economic Turmoil

–Religious Strife/Rise of Christianity

–Lead poisoning

–Poor Leadership

–Civil Insurrection

–Plague

But to try understand the paradigm of Roman collapse, one must look beyond single events and understand the interaction between Rome and its energy systems.

In the ancient world, nearly all power was derived from the sun in the form of agriculture. The power collected from agriculture was renewable in the sense that a certain quantity could be collected and used on an annual basis. Storing energy in this form for any substantial length of time was not possible, so society had to function within the boundaries of the yield it grew each year. During the Roman Empire, there were approximately 9 people living a rural life to every 1 person living an urban life. Today, that ratio is closer to 1:1 (in the USA, it’s 1:3). Ancient populations could not allow for such a ratio simply because of the low marginal return of human/animal based agriculture.

All of the ancient world’s social complexity- the religious institutions, the armies, the governments, the urban and nonproductive citizenry- were supported on the relatively low marginal yields of annual human/animal agriculture. This had a number of consequences, most notably that ancient society was susceptible to the effects of variants in agricultural output (weather, pestilence, soil salinization, marauders, etc). Ancient society could only exist within the limits of the marginal yield of its agriculture, but when circumstances led to a collapse of that marginal yield, so too did that society collapse. Inversely, ancient society could only solve problems within the capability that the marginal return of human/animal agriculture allowed.

Joseph Tainter in his book, The Collapse of Complex Societies, theorizes that the decline of Rome was due to a fundamental aspect of all complex societies, that the projection of social complexity among the majority of civilizations has been largely the same, that being one of increased stratification and specialization (i.e. complexity), and that eventually society reaches a point where the usual method of dealing with social problems by increasing the complexity of society becomes too costly or beyond the ability of that society.

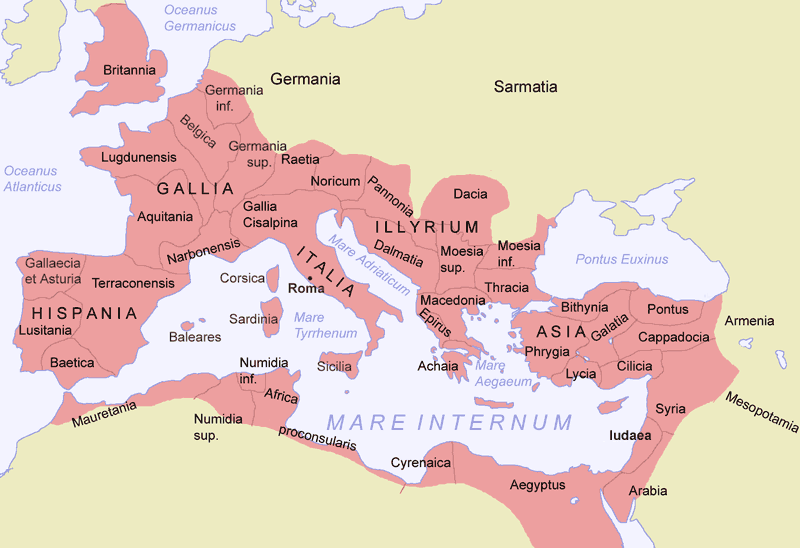

Rome began its life of empire by rapidly conquering the Italian peninsula, during which time it expanded its territory by a factor of 100+:

Through this series of wars (e.g Samnite Wars, Etruscan Wars, Pyrrhic War, and eventually the first Punic War), Rome, like several empires throughout history, experienced the benefits of victorious warfare, those being not only increased territory, but increased revenue, slaves, plunder and resources as well. Roman expansionism in turn required increased social complexity as new regions required governing bodies and a garrison to keep the population subdued. Rome established itself as the only empire to have a consistently standing professional army. During the period following the Punic wars and the wars in Greece, Rome’s success in conquest was sufficient to fund the entirety of Rome’s operating expenses, allowing for the secession of taxation of Rome itself. Further victories against the Seleucid Empire led to Rome remaining as the last major power in the Mediterranean, which was significant during this period due to the prohibitive cost of land trade as opposed to sea faring trade.

The act of warfare itself, however, eventually became costlier as Roman borders expanded to meet stronger rivals at greater and greater distances:

The distances , now no longer adjacent to easily accessible coastline, were making the cost of conquest prohibitive. More to the point, the enemies Rome faced as it grew larger were vast empires themselves and were more than capable of defeating the Roman legions.

It was at this point that Rome had reached a turning point: no longer would conquest be a significant source of revenue for the empire, for the cost of further expansion yielded no benefits greater than incurred costs. Conjointly, garrisoning its extensive border with its professional army was becoming more burdensome, and more and more Rome came to rely on mercenary troops from Iberia and Germania.

The result of these factors meant that the Roman Empire began to experience severe fiscal problems as it tried to maintain a level of social complexity that was beyond the marginal yields of it’s agricultural surplus and had been dependent upon continuous territorial expansion and conquest.

When Rome ceased its expansionist policy of conquest (blue) due to cold facts of cost/benefit, it lost a strong portion of its revenue (indicated by the orange ‘x’) for maintaining Roman Society. As a result, Roman emperors were forced to devalue Roman currency to simply maintain the status quo of the empire. Further economic policies included extremely excessive taxation of Roman peasantry in favor of the Roman urban citizenry and misguided attempts at controlling radical prices fluctuations. The effect of such policy, in conjunction with the intermittent barbarian raids of Roman countryside, was a gradual destruction of Rome’s capital resources: the rural population and its ability to procure sufficient energy to maintain an empire.

And as rural population declined, so too did urban population eventually follow suit:

This process of destruction of capital replaced the former action of conquest to maintain Roman social complexity (indicated in yellow):

The inevitable result of such continued policy was balkanization of the empire as not only did invasion establish new kingdoms, but so too did the Roman populace increasingly wish for relief of excessive taxation (which yielded ever decreasing benefits with the decline of the empire) in favor of simplification associated with local autonomy.

The fact is that Rome had reached a level of social complexity that it could no longer maintain. The empire was too large, had too great of a maintenance cost, with too many (increasing) problems (e.g. economic, productive, military) and too few (decreasing) resources to overcome them.

UrgentEvoke Archive: A treatise on the meaning of Evoke, from a pessimistic perspective

Original post: http://www.urgentevoke.com/profiles/blogs/a-treatise-on-the-meaning-of

For those who are not familiar with UE, it was a site where people could blog for points on the issue of the week. The website catered to optimists, children, and the generally naive. After a certain time there, I decided to add a bit of pessimism to the mix. I had just recently finished Joseph Tainter’s book: The Collapse of Complex Societies, so it influenced heavily on the article below.

—————————————————————-

Subtitled: An explanation as to why I’m a Doomer.

“There’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

Shining at the end of every day

There’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

And tomorrow’s just a dream away”

Friends, bloggers, fellow Evoke agents, lend me your eyes.

I am writing this blog to expand upon the very purpose of Evoke. No doubt you already have an idea as to its purpose as defined in the mission statement, or in the result of actions taken by the members of the community, but I want to apply a theme to the overarching concept of Evoke and all similar communities and their raison d’être.

Plainly put, that theme is maximization. Human population exists on this planet with varying levels of comfort (i.e standard of living), but that population already has the requirements for merely existing. The goal of many here is to maximize the standard of living among those that are just above existence levels (as perhaps opposed to subsistence or more ideally, flourishing). The methods they seek to use vary in type and scope, but regardless of the method, they almost invariably have one similar characteristic. They seek to solve a problem without removing the need for a solution.

Before I expand on that thought further, I first want to address the premise of solutions. Human society exists largely for the purpose of pooling resources to solve problems. The problems that face human societies are innumerous in quantity and infinite in scope. Sustainability, it can then be said, is never a point that is reached. Sustainability means always solving new problems. Sustainable society can never reach stasis. But why solve problems at all? Human society, like any system, has an input/output ratio. The input aspect consists of the ability of society’s population to procure energy (i.e. the means of support). The reason I say energy, and not ‘goods and services’, is because everything in this universe utilizes some aspect of energy. Energy is the underlying basis of all resources and actions of a population. The output aspect consists of all the benefits that society confers to the residing population (either real or perceived). The population largely agrees to provide input into society because the benefits they receive back are worth the time, effort, and physical resources that input requires. When the benefits of a society no longer exceed that of the input required, two things can happen. The society can either coerce the population into continuing with an unfavorable ratio of benefits/cost or the society can choose to no longer pay the cost demanded for the continuation of that society. The result is a collapse in the complexity of human society and the loss of the benefits that society conferred.

The progressions of societies largely follow the same trajectory, that being one of diminishing marginal returns.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/28/Average_and_marg…

I will use the analogy of an oil field, it being a very good example of raw energy, to describe a system that is based upon the exploitation of energy. This idea was excellently covered in Chris Martenson’s video linked here: http://www.chrismartenson.com/crashcourse/chapter-17b-energy-budgeting

When an oil field is discovered, it uses energy in the processes of discovery and creating infrastructure, yielding an increasing margin of return (profit) as the field is increasingly exploited. As some point along the timescale of an oilfield, however, the rate of growth of the margin of return ceases to increase, and begins an inexorable decline of surplus energy. When the margin of return reaches a point where it takes one unit of energy to extract a unit of energy (i.e. the margin of return is zero), there is no reason to further exploit the oil field and production ceases. All the benefits that were yielded from this system of surplus energy are lost with it and the capital resources (the left over energy resources now not being invested into further production) are usually cannibalized. Now let’s overlay the idea that society, also, as a dynamic input/output system based on energy experiences diminishing returns. Upon experiencing a problem, society seeks solutions. The solution that is easiest and cheapest is usually the one that’s used first. The marginal return of the benefit/cost ratio of simple solutions for simple problems is usually very good. But growth or time itself will bring about more complex problems, in turn requiring an increase in the costliness of the solution. Organizational structure and complexity of society increases as each problem/solution also increases in complexity.

Society thus engages in a process, where an increase in complexity and organization is constantly needed to maintain a system being faced by more complex problems, but yielding an ever decreasing marginal return (surplus) to be able to deal with such problems. Societies may come across innovations for new sources of energy, as was the case with coal, oil, fission, etc, in which case the marginal return graph may have multiple “humps”, but in the end, there is an inevitable decline in the marginal product.

The law of diminishing returns applies across the board, to virtually all aspects of human societies, old and new. It even applies to the very strategies of problem solving. So the R&D process of solutions increase in tandem with the complexity of problems/solutions themselves, furthering the cost upon society at large. Solutions to declining marginal yields, it can be said, have marginal yields themselves and declining marginal returns are formulated by the decisions to choose less costly solutions prior to more costly ones. The very progression of society is from simple to complex. A few examples would be farming rich, fertile fields before marginal ones, or exploiting light, sweet crude oil before heavy, sulfated crude oil, or fishing rich areas of the sea before poor ones, etc. That’s why I find the idea of simple solutions to problems of increasing complexity so silly. There is [almost always] never a simple answer, only a trade off of costs and benefits.

When the marginal product in society begins to decline, by definition that society will be commanding a declining surplus (as a percentage of input, although as a quantity, it may be greater than in the past) and at the same time will have to be allocating an ever increasing portion of the energy budget simply to maintain organizational institutions (brought about as solutions to previous problems). With every advance, the difficulty of the task is increased and society is less capable of providing subsistence in the future. The result, in the words of Malthus is that “…exponential growth is needed to maintain constant progress.”

Human societies are victims of their own success. Society trends towards complexity and a marginal productivity with an increase in specialization/differentiation. They do this because the benefits outweigh the cost. But the very process of increasing complexity requires increased amounts of energy and resources and greater integration and organizational hierarchy. The result becomes a positive feedback loop where succeeding in solving problems only creates more damning problems down the road. Yes we can give everyone access to fresh water, and yes that is a good thing, but the increase in population also means an increased strain on resources. This increase in population impacts on other segments of society that otherwise may have been stable, but now require even greater resources and new solutions. Maybe it is possible to empower women across the globe to be man’s equal in society (again, obviously a good thing), but now you are increasing resource consumption of a large percentage of the population upwards, again creating further strain. Every solution has unintended consequences. Dr. Albert Bartlett addressed this thought when he so aptly pointed out that the very aspects of society that we admire (health care, safe food & water, traffic laws) all contribute to increasing the population strain, whereas those we don’t admire (war, famine, disease) relieve the stress. The very existence of complex society has allowed human population to exceed that, which would never have been otherwise attainable. That’s why the phrase “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” is so applicable.

The movement towards sustainability largely ignores that even “sustainable societies” collapse. History is actually rife with it. From Rome to the Mayans, they all were relatively sustainable agricultural civilizations. Their energy, in the form of food crops, was entirely renewable, and it let them last hundreds of years. But even sustainable societies are susceptible to the accumulation of stresses. These cultures didn’t decide to increase complexity (e.g. raising larger armies, or increasing peasant taxes, or debasing currency, etc.) because they wanted to or because they were stupid. They were forced to do so or face the dissolution of society. Regardless of the problem (and people can point out all the specific problems they want to, but it doesn’t matter), they would have faced an infinite number of problems, requiring ever-greater complexity, in turn requiring ever-greater energy. Equilibrium in human society does not exist. There will always be one more problem to overcome that requires the balance to be shifted.

The absolute worst aspect of those who attempt to be sustainable, but miss the big picture, is the desire to maximize the evolutionary process of marginal yield (i.e. taking complexity as far as it can go for maximizing actual yields [of numerical quantity as opposed to maximized marginal yields which create surplus, i.e. breathing room, valued as a percent]). They want to make sure everyone has… whatever, pick something; it really doesn’t matter. The end result is an increase in population and in turn increases impaction on other areas. Maximizing the marginal yield process for maximum actual yield of quantity leads to no margin of error or room for expansion, hence upon the need for a solution to a new crisis (or even simple productivity fluctuations), current sustaining product must be undermined (capital resources are cannibalized) simply to attempt to solve a problem. The result is inevitable collapse of societal structure.

Collapse of societal structure becomes a logical choice to members of a societal population when dissolution from society results in a greater marginal profit in their lives (or in a subset society). Extreme costs for sustaining society (i.e. maintaining the status quo) means collapse becomes the economical solution and concurrently declining marginal returns makes increased complexity less attractive. Joseph Tainter, whose works I have largely based this thesis on, pointed out that the paradox of collapse is that a drop in complexity yields a rise in the marginal return on investment and that “under a situation of declining marginal returns, collapse may be the appropriate response… whereas economic intensification is not [an understandable response].”

To avoid collapse and try to maintain some semblance of stability, society will often choose to endure a situation of unfavorable margins of return, as previously stated through coercion. The result is an increase towards social tyranny. Tyranny exists in this situation to prevent the dissolution of key pillars of society, who would otherwise have chosen to reject complex society in favor of the increased margin return of simplification. This partially results from the broader part of society refusing to accept a loss of complexity in their own lives (either justifiably or not). Societal hierarchy, to solve both issues of breakaway core aspects of society, yet hazardous internal disaffection as a result of loss of surplus marginal product per capita, adopt tyranny, that both suppress through force, yet appeases through the “bread and circuses” model. In this instance, sustaining society does not confer freedom or liberty, which may have been the lure into the society. Originally, population members may have been allowed the liberty to do things within society because of the excesses of the marginal return. They did so in a preference to the dangers of an anarchist lifestyle, in terms of productivity, health, and physical safety. The idea was that the large leeway in freedom to do something, while having the safety nets of society was preferable to having total and complete freedom (to do anything, right or wrong), but having a shorter, and often violently abrupt lifespan. The irony is that as society progresses into declining returns, there is also a declining amount of freedom (cost), but not a comparable increase in safety/lifespan (benefit), and the population is left choosing between being “damned if they do and damned if they don’t.” Look around you. If you live in a first world nation, & especially the United States, that should be obvious.

Collapse of society in today’s world, as it was in societies of the past, means a collapse of the population that societal structure supports. This is the conclusion I have reached, and it’s not one I have taken lightly. The difference between collapse today and collapse of the past, as proposed by Joseph Tainter, and concurred with by myself, is that collapse this time will be global. There is a subtle reason for this, and I will illustrate it using an analogy of several communities on an island. Let’s say there are 5 of them. Four of them many would consider sustainable. Their population is at replacement levels. They grow enough food for themselves to eat comfortably and perhaps then some. Every other aspect of society is at a quality where it has no impact upon population. But in the last tribe, their population growth is quite large, and they frequently face crises where they do not have the means to support themselves. They may first attempt to ask for assistance from the other tribes and the tribes just may subsidize this tribe’s behavior, perhaps out of humanitarian reason, or perhaps out of fear. At any rate, there will come a point where that tribe will not be able to support itself and the other tribes will either be unwilling or unable to give assistance. The result, as proven historically is a violent confrontation of acquisition of another “tribes” resource base. Assuming the behavior yet goes unchanged, this will continue until the whole island system collapses. Even if it had not been violent, or if the problem had not been one of population, the result would have eventually, given enough time, been the same as a crisis impacts one group, forcing it to confront another. The tribe(s) suffering the crises could have chosen to collapse to a level where marginal return was great enough to weather the storm, but doing so, especially in a situation where other tribes face similar problems (or they may not, but might simply have a growth behavior where expansion into the collapsing tribes base is a ‘solution’) means the possibility of being subjected to the domination of other groups who refuse to collapse alongside of you. As put by Tolkien: “It needs but one foe to breed a war, and those who have not swords can still die upon them.” What really factors into the equation is the concurrence of problems (which certainly affects global society today), for that is what is (and has in the past) driving competition as opposed to cooperation. The thing to draw away from this is that no society in today’s world is going to accept a collapse strategy (e.g. as espoused by Richard Heinberg in Powerdown) over a continued escalation of the social complexity dynamic, even if returns become unfavorable. The mere existence of other states becomes the reason for continued complexity. As put by Tainter: “Competition makes controlled collapse unfavorable, making unfavorable marginal returns favorable.” This continues until the whole world is faced with problems that are beyond the scope of society to solve, leading to a rapid global collapse. This time, the cost will most likely be measured in billions of lives.

This is the purpose of Evoke, and all similar communities, who like broader society, seek ways to solve problems of ever increasing cost and complexity to avoid what is inevitable collapse. They seek solutions for problems that inevitably, given enough time (and I don’t think that much more time is going to be needed), have no permanent solutions. The problem is the need for the solution. There is no way to achieve that without collapse of much of what society holds dear. If collapse is indeed inevitable, then my hope is that it comes sooner, rather than later, if for no other reason than to reduce human suffering and environmental cost. And that is why I am a Doomer.

-Iron Helix

Man has a dream and that’s the start

He follows his dream with mind and heart

And when it becomes a reality

It’s a dream come true for you and me

So there’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

Shining at the end of every day

There’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

Just a dream away!”

Addendum #1: Some of the comment responses for the article:

A)

Quote:

—————————————

With Malthusians I agree: there is a limited amount of resources and raw and everything else comes from them and inventions can´t change that. Yet I disagree with the simplistic approach that high poopulation and high density will ALWAYS go against the availability of resources and standards of living. For example Monaco has the highest population density in the world and also one of the highest standards of living http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/popdensity.htm

—————————————–

(perhaps it´s Bangladesh so again there is no simplistic answers)I’m posting this from a comment I made in another blog:

A point that I was trying to make, but may not have come across as clear, was that population is a big factor in society, yes, but it’s not necessarily the root problem. More importantly, the problem is a lack of surplus energy to support that population. When a society is not kept in check as to having a sufficient marginal return (i.e. margin of error) to overcome problems, then those problems will overcome society. Applying that to population dynamics in today’s societies, population growth does not yield a corresponding growth in surplus energy but rather a decline in available energy per capita, meaning human society is less able to cope with future problems by having more population. That does not mean that human population couldn’t grow or be at today’s levels, but for that to be the case, that society needs to have sufficient surplus energy (i.e. marginal yield) for future problems/solutions and the complexity increase required. Today, energy returns are at a precipice. Population has been allowed to grow without adequate support. The margin of return on energy in the future (for whatever reason you want to give) is looking to be less than it is now or even during the past; this is also coupled with a peaking of supply production (peak oil, peak coal, peak uranium, peak top soil, etc). Again when referring to energy, I am using the term in a broad sense. It can apply to many critical aspects of society: energy supplies (of course) food, water, disease control, etc. If future margins of return are looking slimmer, but population in turn is growing, that means a larger population having a smaller margin of error. At some point, that will not be allowed to continue (either voluntarily or involuntarily).

If this were a computer simulation, and there was a cheat for infinite energy, then population would have, for all intents and purposes, an infinite marginal yield (and thus a very large safety net), and would even be able to grow under that circumstance since increasing population does not affect the marginal yield and the corresponding societal functions… that is to say so long as there are no other limitations (which there would be of course).

B)

There are always alternatives, but that largely depends upon what your goal is.

If the goal is to increase the population’s lifespan and its standard of living, then that’s largely contrary to easing the strain that population is causing on societies’ surplus. Of course it would be ideal if you could do both, but if we’re already at a point where marginal yields are well into decline, with little prospect of that getting better, due both to the increase input cost as well as a decreasing ability to pay that cost, then trying to accomplish both will actually solve neither and will only have increased the cost of society through the increase of complexity while attempting to solve the issues.

Optimists will often adopt the cornucopian model to get around this. The Venus Project is a good example of cornucopian thinking. When presented with this issue, the easy solution is always unlimited energy, because with unlimited energy you can both increase the benefits of society and lower the cost (unlimited energy begets cheaper energy).

The real world does not work that way however. Accepting the premise that with a limited supply of surplus energy at our disposal, we can do two things. We can either use our diminishing surplus to attempt to maintain the energy supply society requires (e.g. through alternative energy) or we can use it to maintain the increasing cost of the benefits of society. Doing both would be counter productive, as ‘new energy’ is consumed by ‘new benefits’, and the marginal yield decreases further, eventually to a point where society is no longer worth supporting.

The only true sustainable option is sacrificing benefits, for sustaining the benefits first requires the energy to do so, and unless drawing down your energy supply until the marginal yield is zero is the plan, only focusing on maintaining the marginal yield through new energy subsidies makes sense. The next serious question is how well the population will take a loss of benefits, for that largely means a loss of lifespan and standard of living. Unless society is going to be adopting a coercion method of enforcing cohesion during a loss of benefits (i.e. an unfavorable margin of return), I fail to see how society will be able to increase the energy supply margin (through an additional energy subsidy of renewable technology) without collapse of the whole system and the population along with it.

If a dictator was placed in control of the world (and that’s not something I would readily support, believe me), I bet a lot could be accomplished to mobilize the remaining surplus of society to continuation (e.g. enforcing renewable investment, forcing people to have an increased part in food/water production, decreasing the excesses of certain areas of society, controlling population growth, etc.). But I have serious doubts as to whether a totalitarian model would be successful in maintaining control. It goes against too much of what society (particularly 1st world) has espoused as values (e.g. liberty). You should ask yourself how much [freedom] you would be willing to sacrifice to avoid a collapse situation. Myself, I can’t imagine it happening, but there is no way to hold on to what has been built without it. Hence my firm belief that the result will be a collapse that results in a large loss of life. There’s the chance that might not happen, but it would require either an evolutionary monolith in energy procurement (e.g. feasible fusion) or a coercive, totalitarian system enforcing the acceptance of loss of benefits yet attempting to expand the surplus margin in the area of renewable technologies to subsidize the declining margin in conventional energy.

An optimistic hope would be that everyone already recognizes the situation and voluntarily decides to cut back on societal benefits and accept a lower lifespan/standard of living, while yet agreeing to contribute greater amounts to the maintenance cost society requires. If the human race had a hive mind like bees, I could see this happening… maybe. But then again… I’m a pessimist.

C)

Quote; “The thing that must be considered is that in turn you propose population control through elemenating those who are not benificial. ”

Where exactly did I propose to eliminate people? What I was saying was that continued population growth in society does not equate with growth in the energy returns for society. At some point, and I believe that point has already been reached, continued growth leads to a decreased ability for society to sustain itself. “Eliminating people” is not going to fix that. If anything, I’d imagine it would only hasten collapse. One hopes that population levels will level out on their own, and there may be some evidence for that, at least in some areas of the world.

Quote: “My only problem is that your assesment that Rome was sustainable. In actuality Rome fell for several reason and the primary one was that they over extended economically and roman citizens didn’t want to go to war. They got comfortable. They had to hire mercinaries for the continious expansion. Mercs drained the banks and eventually the system fell. ”

By sustainable, I was referring to the energy systems that Rome was dependent on as opposed to modern day energy systems. Rome’s collapse was due to the declining marginal yield process. That process exhibited itself through various ways (e.g. debasement of currency, barbarian wars, etc). Speaking to Roman wars specifically, the marginal yield process was such that Rome no longer expanded through conquest due to lack of sufficient returns. Further war only lead to a drain on Rome’s treasury, whereas previous wars created additional surplus. When Rome reached its expansion limit, it could barely maintain its border due to the declining surplus, not only due to no further expansion, but also due to increased incorporation of the regions of the empire, the result of which was decreased exploitation in some instances or increased rebelliousness in others. The overall reason was that Rome’s surplus was eventually insufficient to maintain the demands of society. The result was collapse.

Addendum #2: A response to a separate blog where I expounded upon the article:

Quote: Increasing complexity, advancing technology and social density are already essential and necessary to maintain the world’s population being alive today. A thing as simple as a pencil eraser couldn’t exist without an enormous alliance of different clever people doing different clever things with rubber and metal using an array of machines to get it all into your pencil at the end of that particular interconnected chain of chains. And that pencil could write an idea or invent a technology that could change lives and change the world.

[…]

I think that on balance it is the very population density and technological change that comes with many problems that is the solution to the very same problems. Without rapid exchange of knowledge and ideas, we go down a path of stagnation which resulted in such great historical epochs as the dark ages, a thousand year pause on human development in which most people in Europe lived lives of quiet rural misery as serfs. Technology advancement and our collective wisdom go hand in hand, and the only way out is through.

What’s unfortunate is that you are refusing to address the cost aspect of complexity/technology/social density. Yes, there are obvious benefits to those things, but only to a point. Somewhere along the line of increasing complexity, the benefits are no longer going to yield a ratio that justifies the costs.

This topic warrants further explanation, so I am going to provide some visual aids to assist in my discourse.

It is a common misconception to think that marginal growth in either complexity, technology, or most anything else looks like this:

This is based on a common assumption that “technology begets more and better technology”. What is not understood is the idea of the marginal yield process.This is a general diagram of a marginal yield curve:

This represents the evolution of net yield with the increase of complexity. The curve is divided into 4 phases of growth. The first phase represents the initial investment period, where the rate of change of the growth of the yield curve is positive. The second phase represents the period where the rate of change of the growth of the yield curve becomes negative, however, the growth itself is still positive until the end of phase 2, where it peaks. Phase 3 represents the point where the rate of change of growth for the yield curve causes the marginal yield to decline. The yield itself is still positive, however as a surplus percentage, it is decreasing. Phase 4 represents the period where the decline of surplus peters out to zero. This is due to a decline in motivation for continued investment as further investment yields less and less benefits.This is just a generalization of the marginal yield process. When observed on case-to-case basis, sometimes phases 1 and 4 are nonexistent, in which case the curve may look like this:

Note that it is possible for the marginal yield to go negative. When this happens, the capital resources are cannibalized, and each successive cycle of investment yields a decline in actual product, until there are no more capital resources. When the marginal yield becomes negative, the investment cycle is doomed. The amount of time that it continues is only dependent on the extent of the amount of capital resources that are being cannibalized. Negative yields are uncommon, and are allowed to happen only when the yields are valued beyond their investment worth.When viewed more broadly, however, we must take into account innovations as opposed to simple increased complexity. When viewed graphically, it may look something like this:

Innovation is usually spurred by a decline of previous marginal yields. Each curve represents one aspect of the complexity dynamic of overall society, however when combined together as they are in that graph, there is still a general pattern, even with innovation. If we simply observe the amount of area under all marginal curves, we can extrapolate a total marginal yield of the complexity dynamic. This area itself is a rough marginal yield curve and can only continue with innovation ad infinitum. When the last curve is met and innovation is either too late or is not possible, then the system, if it progresses down the curve, will collapse.What drives society down that curve? Depending on the circumstances, it can be biology, greed, general intemperance (kudos to Jeremy Hogg), the desire for a “better world” as your position takes, compounding stresses, etc. What’s unfortunate is that as society goes further down the curve beyond the peak yield, the more fragile it becomes to a systemic collapse. This is especially pertinent to society when it must depend on the system(s) (e.g. energy systems – one of the most important and most notorious for demonstrating this pattern).

Ideally, the best position to be is where the marginal yield is at its peak (the tail end of phase 2). It is a dangerous mistake to think that because you have a greater gross yield as you go further down the curve, the decline in marginal yield is justified. Doing that creates a fragile system that is much more vulnerable to collapse.

Addendum #3: Visualizing Doom

Expanding on marginal yields, I want to put it in a visual context for everyone:

Notable things about this graph are that as time progresses, the distance between gross energy (blue) and net energy (green) increases and the ratio of gross energy (capital expense) to net energy (the marginal yield) increases. The result is not only less total energy available due to the finite nature of conventional energy sources (causing the peak shape), but also a decreasing surplus yield from those sources, making them less worthwhile to exploit. Another point worth mentioning is that peak net energy precedes peak gross energy. If gross global energy supplies are peaking, then that just puts us that much further behind the 8 ball.Here’s another one (it’s a bit more colorful):

And again:

So, given that society needs energy, how is society even going to be able to maintain its energy supplies when the benefits society confers demands an increasing share itself? Society will not be able to do both. Increasing societal benefits means increasing the energy strain, so any new benefits (e.g. raising global standards of living) are largely going to consume whatever new energy is brought online.

Anyways… have a nice read.

-Iron Helix

Addendum #4: An article linking the above with the Gulf oil spill.